|

|

|

|

|

|

An ancient history

An ancient history

From the book "The

Aeolian islands" published by the Tourist office - Lipari

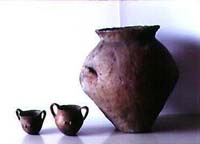

The history of the

Aeolian islands is basically identical to that of the island of

Lipari. The first human settlers came there from Sicily in the

Middle Neolithic period (from the fourth millenim BC), in small

rudimentary boats. They were farmers ans stockbreeders and also

made and decorated pottery and were skin flint cutters: they had

found deposits of Obsidian on the island, which was then the

most precious mineral. The history of the

Aeolian islands is basically identical to that of the island of

Lipari. The first human settlers came there from Sicily in the

Middle Neolithic period (from the fourth millenim BC), in small

rudimentary boats. They were farmers ans stockbreeders and also

made and decorated pottery and were skin flint cutters: they had

found deposits of Obsidian on the island, which was then the

most precious mineral. |

| Black and shiny, obsidian is a very

hard , vitreous volcanic rock that is not produced by all

volcanoes. It was due to these deposits that the

archipelago underwent an extraordinary development in Neolithic

times, leading to the growth of villages and the intensification

of sea trading, for obsidian was used for making much-needed

tools, knives, arrow heads, and blades that were less resistant

than those made of flint but much harder. Large quantities of

obsidian have been found in the Neolithic villages of

Sicily and the Italian peninsula and even on the coasts of

southern France and Dalmatia. |

Pumice, a porous variety of obsidian, is also produced by

volcanoes and has the same composition ; it is of a greyish

white colour and is so light that it floats on water. It was

used in prehistoric times as an abrasive stone for finishing

tools. Today it is used as an industrial abrasive, in concrete

and for soundproofing. The large pumice quarries that have

pitted and whitened the slopes of Monte Pilato have provided

work for generations of local inhabitants, although quarrying

has shown a sharp decline in recent years. Pumice, a porous variety of obsidian, is also produced by

volcanoes and has the same composition ; it is of a greyish

white colour and is so light that it floats on water. It was

used in prehistoric times as an abrasive stone for finishing

tools. Today it is used as an industrial abrasive, in concrete

and for soundproofing. The large pumice quarries that have

pitted and whitened the slopes of Monte Pilato have provided

work for generations of local inhabitants, although quarrying

has shown a sharp decline in recent years. |

| The oldest settlements have been found

on the plateau areas of Castellaro Vecchio, while the

early centuries of the first millenium BC saw the growth of the

first settlement on the Rocca di Castello. Druring the period in

which the obsidian trade was in its height and economic

wellbeing led to population growth, the settlement expanded onto

the Diana plateau, at the foot of Rocca di Castello. |

| At the end of

the third millenium BC, in the early Bronze Age, new settlers

came to Lipari and the Aeolian Islands, thus injecting new

lifeblood into the economic and cultural life of the area.

This reawakening was due to the establishment of regular

contacts with the principalities of Mycenaean Greece, whose

navigators boldly explored the western seas in search of the raw

materials needed to maintain their power and ensure their

survival. During those times the islands were visited by

Myceanean peoples of Aeolian origins who had already settled in

Metapontus and used the islands as outposts for controlling

trading routes through the strait of Messina. The

islands have retained the name deriving from these Aeolian

travellers. The myth of king Aeolus, lord of the winds, that is

mentioned in Homer's Odyssey also derives form Aeolian

culture. |

During the thirteenth century BC, the islands were settled by Ausinian

peoples from the coasts of Campania, who brought with them the myth

of King Liparus, which is were the town's name derives from.

The islands underwent a process of depopulation during the tenth

centuries BC - possibly due to rivalry between different races

for supremacy in the lower Tyrrhenian Sea - and they remained all

but deserted for several countries. During the thirteenth century BC, the islands were settled by Ausinian

peoples from the coasts of Campania, who brought with them the myth

of King Liparus, which is were the town's name derives from.

The islands underwent a process of depopulation during the tenth

centuries BC - possibly due to rivalry between different races

for supremacy in the lower Tyrrhenian Sea - and they remained all

but deserted for several countries.

During the fiftieth Olympiad (580-576 BC), Lipari was colonised by

some Greeks of Doric origin from Cnidus and Rhodes, who

were led by a Heraldic named Pentathlos and had earlier made an

unsuccessful attempt to found a colony at modern-day Marsala. The

new colonists were the first and foremost faced with the need to

fight off Etruscan incursions. They therefore created a powerful

fleet, which led them to many victories and ensured them maritimes

supremacy. They used captured booty to erect some splendid votary

monuments in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi - over forty bronze

statues whose bases can still be seen. The ships of Lipari dominated

the lower Tyrrhenian area and in 393 BC they intercepted a Roman

ship on its way to Delphi with a large gold urn constituting a tenth

part of the booty taken following the sack of Veii.

But their chief

magistrate, Timasiteus, made their return it because it was a sacred

offering to Apollo, the god worshipped by the people of Lipari. In

427 BC, during the first Atenian expedition to Sicily, the people of

Lipari entered into an alliance with the Syracusans, perhaps of

their common Doric origins. Thucydides reports that they were

attacked by the fleets of Athens and Regium, though with serious

consequence. But their chief

magistrate, Timasiteus, made their return it because it was a sacred

offering to Apollo, the god worshipped by the people of Lipari. In

427 BC, during the first Atenian expedition to Sicily, the people of

Lipari entered into an alliance with the Syracusans, perhaps of

their common Doric origins. Thucydides reports that they were

attacked by the fleets of Athens and Regium, though with serious

consequence.

In

the carthaginian expedition of 408-406 BC, Lipari was again allied

with Syracuse: However, it was attacked by the Carthaginian general

Himilcon, who took control of the town and forced its inhabitants to

pay a randsom of 30 talents. Once the Carthaginian had left, Lipari

again became completely independent. |

During the time of Dionysius the Elder, Lipari remained an ally of

Syracuse and later of Tindari. In 304 BC, the island was

attacked by Agathocles, who imposed a tribute of 50 talents,

which he then lost while sailing to Sicily in a storm that was

attributed to the anger of Aeolus.

Lipari

later fell under the dominion of Carthage and was still in

Carthaginian hands at the outbreak of the first Punic War. The

archipelago became a solid Carthaginian stronghold because of

its excellent ports and important strategic position. |

| In 262 BC,

the Roman consul Cn. Cornelius Scipio, mistakenly

believed that Lipari could easily be taken and was captured with

all of his men by Hannibal. In 258 Aulius Atilius

Calatinus besieged Lipari. In 257 the waters around the

Aeolian Islands were the site of a fierce battle between the

fleets of Carthage and Rome. Lipari was conquered by the Romans

in 252 BC. Razed to the ground with "inhuman cruelty" it lost

independence and economic prosperity. This was the beginning of

a period of great decline. |

| The island still continued to

make great profits from alum, which was probably already being

extracted in the Bronze Age on the island of Vulcano and for

which Lipari held the monopoly in ancient times. The excellent

thermal springs in Vulcano and Lipari were very popular and also

very famous in Imperial Rome. Cicero wrote of Lipari and of the

injustices it suffered at the hands of Verres. |

| The Aeolian Islands were of

great strategic importance during the civil war between Octavian

and Sextus Pompey. Lipari, was fortified by Sextus Pompey and

conquered by Octivian's admiral, Agrippa, in 36

BC. He made the island of Vulcano his naval base during the

operations preceding the sea battle at Milazzo and for his

subsequent landing in Sicily. On this occasion, Lipari

again suffered devastation and disaster. It would appear that

the island subsequently enjoyed the status of municipium and it was defined by Pliny as oppidum civium romanorum.

|

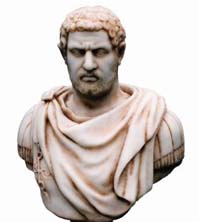

| There is no mention of Lipari during

the entire period of Imperial Rome (first-fourth century AD).

All we know is that having his father-in-law Plautianus killed,

the Emperor Caracalla sent his wife, Plautilla, and his

brother-in-law, Plautius, into exile there for the rest of their

lives. During the Christian period, (perhaps from the fourth

century AD), Lipari was an episcopal see and the relics of Saint

Bartholomew were venerated in its cathedral at least as early as

the sixth century. According to traditions dating back to

Byzantine writers, the relics were brought there from Armenia by

miracle |

|

| In the late Middle Ages, Lipari was

the destination of pilgrims from near and far. This was the

period in which a great variety of legends grew up around the

Aeolian Islands, particularly Lipari and Vulcano. The crater of

Vulcano was said to be the mouth of hell, in which the souls of

the wicked were burned. There is also a well-known legend

narrated by Saint Gregory the Great : apparently a local hermit

saw the soul of Theodoric, the Ostrogoth King thrown into

the crater on the day of his death by Pope John and the

patrician Simmac, whom had had murdered. |

| Other legends concerned Bishop Agathon and Saint Calogero, the

hermit who rid the island of devils and caused the water to flow

from the spring that bears his name. During the early Middle

Ages, the volcanoes on the island of Lipari suddenly became

active after being dormant for decades. It was then that new

craters opened on Monte Pelato, which threw out enormous masses

of pumice, and on Pirrera, the volcano closest to the town, from

which a flow of obsidian erupted. |

In

839, Lipari was attacked and destroyed by

Muslim marauders, who massacred many

inhabitants, took others as slaves and

violated the relics of Saint

Bartholomew. The relics were then piously

gathered together by some old friars who had

escaped the massacre and transported to

Salerno in the following year and

subsequently to Beneventum. Lipari remained

almost completely deserted for several

centuries until the Normans reconquered

Sicily and sent Abbot Ambrogio and a small

group of Benedictines to settle on the

island in 1083. A small community began to

form again around the monastery, the remains

of which can still be seen at the side of

the cathedral. In 1131, the episcopal see

was reconstituted on Lipari and united with

the see at patti. In 1340, Lipari fell into

the hands of King Roberto I of Naples. In

1540, the town was sacked by the ferocious

pirate Ariadeno Barbarossa, who took the

unfortunate inhabitants into captivity.

Lipari was later rebuilt and repopulated

under Carlo V and after that its fortunes

followed those of Sicily and the Kingdom of

Naples. In

839, Lipari was attacked and destroyed by

Muslim marauders, who massacred many

inhabitants, took others as slaves and

violated the relics of Saint

Bartholomew. The relics were then piously

gathered together by some old friars who had

escaped the massacre and transported to

Salerno in the following year and

subsequently to Beneventum. Lipari remained

almost completely deserted for several

centuries until the Normans reconquered

Sicily and sent Abbot Ambrogio and a small

group of Benedictines to settle on the

island in 1083. A small community began to

form again around the monastery, the remains

of which can still be seen at the side of

the cathedral. In 1131, the episcopal see

was reconstituted on Lipari and united with

the see at patti. In 1340, Lipari fell into

the hands of King Roberto I of Naples. In

1540, the town was sacked by the ferocious

pirate Ariadeno Barbarossa, who took the

unfortunate inhabitants into captivity.

Lipari was later rebuilt and repopulated

under Carlo V and after that its fortunes

followed those of Sicily and the Kingdom of

Naples.

|

|

|

|

|